Here we go again! The chariot story is circulating anew on the Twitterz. In not one but two strings, well-meaning authors are attempting to persuade us that the earliest styles of vehicles pulled behind beasts of burden ultimately set the standard from ancient times up through the space program.

So say these champions of consequential causality, the span of two horses side-by-side (about five feet) was the original measure of uniformity. Roman roads were thus created to accommodate wheeled carriers of this width, which then spread across Asia, Europe, and the Americas. When roads became railroads, all the tools and surveys were standardized to continue engineering such widths.

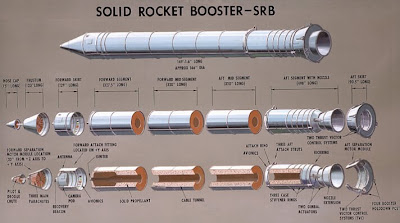

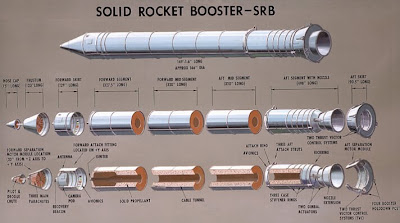

When the Space Shuttle was being developed, its Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) had to travel by train from their

manufacturer to the launch pad. No matter how large or powerful

NASA may have wanted them, they had to fit on flat train cars, and

through train tunnels. And so the size of modern rocket boosters were determined by ancient Roman horse-drawn chariots.

Such a simple choice in ancient times, and yet, it had a huge impact on the world. Or did it? Sometimes, we just innocently enjoy believing stuff because it sounds cool. (But, you know, don't.)

One of many different designs of chariot

Our brains are primed to enjoy the neat, circular narrative. We love a

satisfying story, and as evidenced by how far these tweet-strings travel

-- often circulated thousands of times, they are almost

impossible to counteract. Case in point, my polite explanation received

only a fraction of the retweets. Even for the most patient of teachers,

the effort is always an uphill battle.

This urban legend has circulated every decade since the Space Shuttle program began in the late 1970s.

The first thing to note is that Romans did not invent chariots. Second, the earliest roads over all kinds of terrain were simply human footpaths. The ground wasn't waiting around to say "hey, I'm a road now!" until chariots were invented (though certainly wheels did indeed carve ruts more effectively).

The third claim is objectively not true. Distances between railroads tracks (known as "gauge") have varied widely over the last two centuries, with three standards in the United States alone. The standard gauge used today is based on engineering practicalities, not ancient Italian equine technology.

Chances are, you will wear a white gown at your wedding. Roman

brides did too. We still use plenty of things invented by the early

Roman Republic and the later Roman Empire: candles, scissors, postage,

showers, umbrellas, heating systems, street lights, rampant economic

inflation, and so on.

So,

to say that ancient standards are still alive in the modern world isn’t

all that exciting. Humans are well-known for sticking with certain

things that work, and equally notorious for sticking with certain things

that don’t.

Archaeological evidence suggests the

existence of chariots in far more ancient cultures: Chinese, Sumerian,

Greek, Persian, etc. The Romans were late-comers, though they

fancied-up chariot production with trigas (pulled behind three horses) and quidrigas (pulled

behind four horses). So, while we can credit their empire with

widespread road systems, they weren't overly attached to the simple

metric of dual-equine-derrieres.

Methods and means of

transportation have, throughout history, been designed different ways to

carry different things and accommodate many different vehicles. Some

have been dictated by creation costs, others by limitations of nature.

From gravel paths to 14-lane freeways, a single lane often accomodates a

car as small as a Mini-Cooper, or an 18-wheel rig.

Commonality of construction is no more bizarre here than the idea that all current automobiles have steering wheels – regardless of brand, model, size, number of doors, or color.

The Romans would have called such specification: "desideratum" – colloquially, that which is essential is desired.

At the height of the railway era, over a hundred US companies

manufactured three different gauges of track, showing a decided lack of

standardization. The Chariot-to-Shuttle tale also assumes that any

tunnel would only accommodate a single set of tracks, or only clear the

train's mass with no room to spare. Also notice the mysterious mountain tunnel

in question is never mentioned by name –- but between where the rocket

boosters are built (Utah) and where they are ignited (Florida), there

are actually 50+ tunnels.

Skepticism is the new black

We could muse at length over the patterns and rhythms of urban legends, but rest assured NASA takes travel into account when designing hardware specifications, but to my knowledge, NASA has never been crippled by the slightly-less-than-five-foot span of railroad tracks. No fewer than 20 companies contributed to the many parts of solid rocket boosters, so even if transport was the main event, much of the hardware is already delivered in segments, and "Some Assembly Required" is already a given on the launch pads of Cape [Kennedy] Canaveral.